Nancy's Story |

| · |

Buffalo, June, 1951 |

| · |

Williamsville, 1953 |

| · |

Williamsville, 1954 |

| · |

Williamsville, 1955 |

| · |

Williamsville, 1956 |

| · |

Williamsville, 1957 |

| · |

Cross Country, 1957 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1957 |

| · |

Santa Ana, 1958 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1958 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1959 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1960 |

| · |

Brookings, 1960 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1960 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1961 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1961 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1962 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1963 |

|

Williamsville, 1956-57

By the time I was five, Dr. Hurley had given me inoculations for smallpox,

diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, scarlet fever and typhoid. The vaccine

for polio was first announced in 1955 and before I could go to kindergarten in 1956, I

had to have shots for that, too.

I did not want the shots, but I had no choice: polio was a deadly and

not-uncommon disease.

In the 20th century, until the vaccine was developed, summer was "polio

season." Poliomyelitis, also known as "infantile paralysis," is an

infectious viral disease that is spread in only one way: human-to-human contact.

The disease had been known for at least a thousand years, but did not become epidemic

until people started living in cities. By the 1930's, it was well understood that

the disease was spread by oral-fecal contact: the "summer" transmission vector

being communal swimming in pools, a recreation that first become popular in the early

1900's.

When my own mother and father were young, the virus that caused polio had been

identified but there was no treatment for the disease nor any vaccine to prevent

it. In 1952, over 55,000 children in the U.S. caught polio. Many victims

were crippled for life, some died helplessly of suffocation after their chest muscles

became paralyzed.

There was a boy named Mark in my class at Washington Elementary who'd had polio when

he was three. He hadn't died of it, but his left arm was withered, as if the polio

had frozen it forever as it had been when the disease took him. In first grade

when we were all still small, it was not very noticeable, but as everyone grew, he began

to look more and more like two different people stuck wrongly together.

Mark could not play baseball, football, dodgeball or any other two-handed sport

because he could not catch; when teams were formed, he was never picked. Even when it

was hot, he wore shirts with long sleeves. His mother fixed his shirts so that

they had one regular sleeve and one that was fitted to his short arm, as if the arm was

okay, just small, but everyone knew the truth was that neither his hand nor his arm on

that side worked at all and there was nothing that could be done to make them right

again.

Boys were not supposed to cry, but in fifth grade, I saw him at recess, watching

unchosen from the sidelines, his good arm wrapped around his bad one, weeping silently

from the ache of wanting to be wanted.

Polio did that to him.

Jon Salk, whose father developed the polio vaccine, was in my class in college. I

heard him mention once that his father chose not patent the vaccine because he wanted it

to be distributed as cheaply and widely as possible so that no child would be crippled

by polio ever again. This decision was remarkably successful: although polio still

occurred in other parts of the world, it was declared extinct in the U.S. in its wild

form in 1994 and The March of Dimes (founded to fund the research and

distribution of the vaccine) turned to the cure of other childhood maladies.

Dr. Salk died in 1995, having spent the last 15 years of his life working to develop

a vaccine for AIDS, an infectious viral disease that was unknown in the 1950's and that

is only spread one way: by human-to-human contact.

When my own children were small, they were not inoculated for smallpox because the

disease had been caused to be extinct worldwide by the World Health Organization, a

branch of the United Nations. My kids did get vaccinated against

measles (two kinds), mumps, chicken pox, fifth disease, shingles, pneumonia, hepatitis,

meningitis, rotavirus and HPV -- all vaccines that had been developed in the intervening

40 years -- as well as diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, scarlet fever, typhoid and,

of course, polio.

Other than having to get more shots, getting ready for kindergarten in the fall of

1956 was fun and exciting. My class was going to be the first in our new school

and there was a lot to do to get ready!

The new school had an indoor gym for playing in the winter, so I got to have a second

pair of everyday shoes. I'd never had shoes with rubber soles before because Mom

was of the opinion that they did not give enough support for the feet, but they were

required for gym. When we got home with my new Keds, I put them and bounced all

over the house like a little kangaroo, enjoying the spring underfoot.

I got four gorgeous new dresses to wear -- one for each day of the week! Two were a

similar plaid: one a combination of black, blue and pale yellow, the other, black red

and green. There was also a pretty dress with tiny stripes of blue and white and

a round "Peter Pan" collar. They all had buttons up the back and a

sash that tied in a bow behind. I had a stiff petticoat, almost like a ballerina's

dress, to wear underneath and hold the skirts out. No one except me knew it, but

there was a tiny pink rose on the front to make it pretty. When I got dressed, I

twirled around in just the slip because it stood out so wonderfully and felt so

elegant. The best dress of all was styled like an artist’s smock and was bright

red with a white collar and a black bow like a scarf. On the front left, where a pocket

might be, it had a black appliqué in the shape of an artist’s palette; five buttons,

each of a different bright color, were sewn on the palette like dots of paint. For the

other day of school when we had gym, Mom got some beautiful red tartan fabric and made

me a pleated skirt, a pair of pull-on pants to wear under the skirt so I'd be decent

while tumbling in gym and a matching gym bag for my wonderful new shoes.

On the first day of school, nothing was quite ready. The construction crew hadn’t

finished putting the glass in all the windows, so the breeze blew through the

classrooms. One day a bumblebee came into the kindergarten class and everyone

screamed while the teacher ran around trying to shoo the confused insect out

again. But by the time the leaves turned, everything was weather-tight, warm and

beautiful. The kindergarten room had linoleum on the floor with all the letters of the

alphabet set in a circle so the class could play marching and singing games indoors when

it was too cold to be outdoors in the winter.

Other than playing with Kathy Kull, I'd had very little experience dealing with other

kids my own age, so kindergarten was the first time that I'd been around any group of

kids my own age. Kathy was not in my class and I don't remember making any

particular friends there. I did, however, enjoy the art projects and the books!

My parents were very dedicated to reading and every one of us was read to twice a day

-- once at nap time and again at bed time. We were encouraged to follow

along and, as soon as we could do so, to read the book ourselves. By the

time I entered kindergarten, I could already read pretty well and could write some as

well, although I sometimes got the order and direction of the letters turned

around:

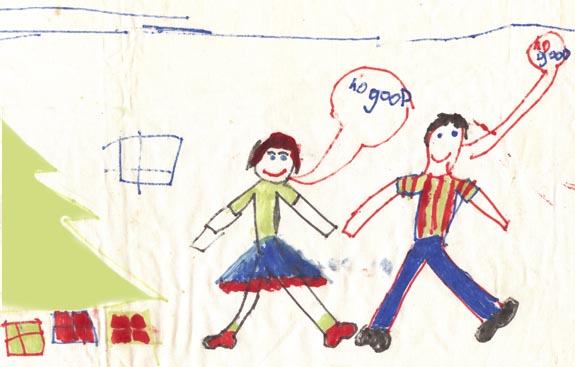

In this Christmas picture I drew, Roy and I are

supposed to be saying "Oh good", not rejecting our gifts

One fall day when the geese were flying overhead and I was hanging my coat in the

closet, the shape of the coat-hangers struck me as being like the geese. It was

only a matter of a few twists of the wire to turn the hook into a head and fold the

sides to be the outline of wings; adding paper to fill in the outline made it possible

for everyone else to see the same thing too. My teacher liked the idea and

soon there was a whole flock of geese hanging from the ceiling, flying south

together. It made me happy at rest time to look up from my mat and see that flock

of paper geese of my design flying overhead.

I went back and forth to school on the school bus. I loved getting home,

running into the house from the cold and smelling what was cooking. One crispy fall day,

Mom made some sort of fruit bar that had an oatmeal crust with a center filling of

apricot jam. I thought it was the most delicious thing I had ever tasted. The dish must

have been a lot of trouble because I never remember her making it again, but even today

I can remember how cold it was that day and how wonderful those warm fruit bars smelled

and tasted.

With the addition of the twins, the house that winter seemed much smaller than it had

ever been before. There was just the one bathroom and even though we had the

diaper service, it seemed that someone was always in it cleaning up after changing

babies. I saw Papa once change a twin, then change the other one, only to turn

back and find the first one wet again. He didn't say anything, but I saw his

shoulders sink and it was clear what he was thinking.

Going to school meant that I had to change clothes a lot more than I'd

ever had to before. Before breakfast, I'd get dressed for school. Most of the

school year in upstate New York, it is cold, so before I left, I had to put on a coat,

leggings, overshoes, mittens, scarf and hat. At school, everything came off and had

to be hung up or put in my cubby until it was time to come home at noon. Then

the over-clothes came back on for the bus ride home. At home the over-clothes came

off again and I changed from my school clothes into play clothes. To go

outside to play in the afternoon meant donning on a snowsuit, hat, mittens and overshoes:

I was old enough to put on my own snowsuit and hang it up afterwards, but

Roy was not and between dealing with wet snowsuits, wet mittens, wet hats, wet scarves,

wet overshoes and wet babies, by end of the spring, Mom had had enough!

As soon as school was out, we packed up and moved to California.

|

|