Nancy's Story |

| · |

Buffalo, June, 1951 |

| · |

Williamsville, 1953 |

| · |

Williamsville, 1954 |

| · |

Williamsville, 1955 |

| · |

Williamsville, 1956 |

| · |

Williamsville, 1957 |

| · |

Cross Country, 1957 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1957 |

| · |

Santa Ana, 1958 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1958 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1959 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1960 |

| · |

Brookings, 1960 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1960 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1961 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1961 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1962 |

| · |

Santa Barbara, 1963 |

|

Santa Barbara, 1962

Crime and Punishment

Every household had a different way of keeping their kids in line. The most

popular method of discipline was to grab the offending child and wallop them on the seat

of the pants until they got the point. By some sort of treaty among the grown-ups,

it was agreed that parents were only supposed to whack their own kids, so one of the

worse things to hear from any adult's mouth was "I'm going to tell your mother

about this!" Most of the parents administered punishment as soon as the

misdeed was discovered, but the Olsen family belonged to the "wait until your

father comes home" school of justice and Mr. Olsen, a big guy who ran a

construction company, used his belt to make sure none of his boys had any confusion

about what they'd done wrong.

Pop was at work five days a week, so most of the transgressions were committed on

Mom's watch. She did not have waste any of her time telling the other moms

about their children's misdeeds because she was the master of the terrifying LECTURE,

delivered to the unlucky culprit in public and on the spot. I think a lot of the

neighborhood, the Olsens included, would have preferred to be walloped by their own

parents than lectured by our Mom.

Whatever the method of discipline was, no one wanted to "get it" and there

evolved a neighborhood code of omertà that rivaled that of the Mafia.

The Morgans had some motorbikes that we were very strictly forbidden to ride.

My sister Joanne particularly lusted after doing so and one day talked her way into

using one in secret. She was wearing shorts, didn't realize how hot the muffler

got and burned herself badly. Every kid in the neighborhood knew and NO ONE

said a word lest she "get it" in addition to suffering the pain of the burn.

The streets were made of asphalt and the sidewalks cement. The latter were

great for skating, but you had to keep a sharp eye out and step over the bumpy expansion

joints that were put there, as far as anyone knew, solely for the purpose of tripping

unwary skaters. Falling down was not only embarrassing, it hurt.

A spill on the rough concrete meant not only pain, blood and gore but at least a week of

ugly scabs on the knees and elbows, a mute public testament to the clumsiness of the

skater.

Some of the area around the Morgan's and Worrell's house was very

steep. For erosion control, this area was planted with ice plant, a succulent that

has bright flowers, spreads easily and requires a minimum of care. Some of the area around the Morgan's and Worrell's house was very

steep. For erosion control, this area was planted with ice plant, a succulent that

has bright flowers, spreads easily and requires a minimum of care.

All ice plant is disgusting, but the kind with large flowers is the most

disgusting of all. Where any decent, self-respecting plant would have leaves, this

kind of ice plant has huge fleshy green prongs that would look perfectly natural only on

an alien from Arcturus. Ice plant's sole redeeming feature is that you can break

off its nasty pseudopods and use them to write on the sidewalk.

Messages written in ice plant were brown and lasted a day or so before fading in the

sun. Some of the neighbors planted a sort of privet hedge that grew quite tall and

that had tasteless purple berries: "tasteless" as in "no flavor".

Every kid had found this out by biting at least one berry and no one had died in the

process, but if they had, their demise would have been a mystery to the grown-ups

because the neighborhood code of silence would have protected the transgressors even

unto the grave.

Berries were only available about half the year, but they were much better for

writing on the sidewalk than ice plant: messages written using berries were darker and

lasted up to a week. Serious sidewalk writing was always done in berry;

minor matters in ice plant.

It was a matter of regret to the entire street that the Fennerns lived in the house

on the corner. Big Claudette was a bully, Kathleen was a sneak thief and little

Kelvin was a positively dire young sadist who threw rocks at anything that moved and who

liked to hide in their privet hedge so he could jump out and push over people who were

skating. We were all sure he'd end up in jail and hoped it would happen

soon. Only Joyce, the next-to-youngest, was normal. Mrs. Fennern

was as nasty as all the kids rolled up together: complaining to her that Kathleen had

swiped the peach-colored peerie boulder I'd gotten from Uncle Lee was something I should have anticipated would be

an exercise in futility, but I didn't expect she'd violate the parental rules of

engagement and slap my face for "Calling my nice Kathleen a thief."

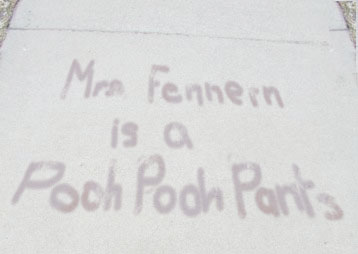

Walking past their house one day, brooding on the unfairness of it all, I picked some

berries and, in a lightning guerilla action, wrote that deadliest of deadly insults on

their sidewalk:

I proceeded on my way, thinking nothing more about the matter.

When Mr. Olsen came home that evening, he found Joyce using a handful of

berries to write on the sidewalk in front of his house. He jumped out of his truck,

grabbed her and asked what she thought she was doing. The question was

unnecessary. Even incomplete, it was clear what the message was going to say:

Mr. Olsen is a Pooh Poo ...

Terrified and crying, Joyce admitted that her mother, furious about

finding such a horrid, FILTHY thing written on her sidewalk, had decided that the Olsen

boys must have done the evil deed and sent Joyce to write a reciprocal and retaliatory

message.

Everyone on the street witnessed Mr. Olsen marching her home.

He was there for quite a while and it was a matter of lively speculation

as to what might have been said. Sadly, there was an adult code also, so whatever

happened in the corner house that evening remained a mystery to us all.

It was probably unrelated, but the Fennerns moved away not long after and

everyone rejoiced. Kelvin, I understand, grew up to be a lawyer and practiced in Ventura,

armpit of the California coast.

I never did get Uncle Lee's boulder back, but I felt at least partially

vindicated. There were probably a few kids who knew I'd written the original

message but I could be sure that, if so, all mouths would be zipped and that I'd be

protected by the code of silence.

|

|